We often read or hear terms like Red, Blue, Purple, Adversarial Emulation and many others almost interchangeably, which often causes confusion in cybersecurity neophytes.

All these disciplines, often partially overlapping each other in their scope, have their place in an organization’s security plan, but it is important to be clear about their strengths and weaknesses in order to take advantage of the former and minimize the latter.

Throughout this article, or series of articles (let’s see how far down the rabbit hole I go), I will try to do my bit on this topic by ,firstly, introducing the Purple Team methodology and then looking into it with a bit more depth.

It is convenient to clarify that this article does not intend to be a lecture on the subject and only aims to make an exposition as educational as possible.

Some background

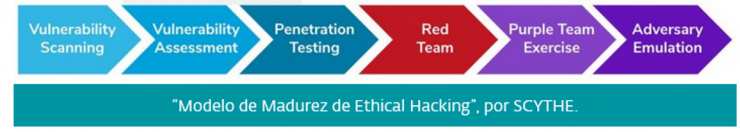

As organizations have matured and cybersecurity has become more and more important, different methodologies and approaches have been developed.

Several years ago (and unfortunately also in some organizations today) cybersecurity was reduced to hardening measures, and gradually detection and response technologies began to be appear.

Subsequently, the development of vulnerability scanning and management tools such as Nessus and OpenVas laid the first stone on the road to offensive cybersecurity.

Faced with the obvious shortcomings of automated tools (they do not adapt adequately to the particular use cases of the infrastructure), specialists in the offensive area began to be needed. Pentesting was born. Pentesters try to find and exploit vulnerabilities in organizations’ systems, with the goal of reporting them up the chain of command.

However, these actions tend to be narrow in scope, and in some ways perform a similar task to a vulnerability scanner but much more granular and deeper.

The Red Team is the natural evolution of pentesting (more oriented towards purely technical penetration), creating coordinated multidisciplinary teams whose goal is to mimic as close as possible the way attackers act (emulation vs. simulation, but that’s another matter) to compromise information security with a holistic approach.

These teams are ideally also staffed with personnel specialized in physical security and social engineering, to increase realism and act on the largest possible attack surface.

What is the problem with the Red Team?

In theory, a good application of the Red Team methodology should produce high-value information for the Blue Team to tweak and tune its detection and response systems according to the reported deficiencies. But this is not necessarily the case.

It has been experienced on too many occasions that the Red Team chain of command sets the objective of compromising as many systems as possible at any cost, which is not per se incorrect, if it were not for the number of perverse incentives it generates.

On the one hand, an analyst who finds a breach in a system is incentivized in certain cases not to give enough details about the exploitation in order to use it again in the next audit and thus repeatedly capitalize the achievement.

On the other hand, isolation of the Blue Team can lead to excessive focus on prevention, detection and response to threats that, due to the particular conditions of the organization and the adversaries targeting it, would not have a major impact on business continuity.

In this sense, a major deficiency that a Blue Team may have is the implementation of measures that are not really effective or adapted to the TTPs of our most likely threats.

Finally, another less perverse shortcoming of segregating Red Team and Blue Team is that after an exercise, the implemented containment, detection and response measures will not be tested again until the exercise is performed, which can often take months.

So, what next?

Next up is the Purple Team, although there is a lot of confusion surrounding this term and not for lack of reason. The name might lead one to think that this is a team of people who perform both offensive and defensive duties. But this is not the case.

Purple Team is a term (with some marketing behind it), which refers mainly to an attitude (a predisposition, if you will) and a methodology aimed at coordinating offensive and defensive operations in the most efficient way possible, in order to minimize the disadvantages mentioned in the previous section.

During the development of coordinated activities, the offensive and defensive teams work interdependently. In this way, the Red Team gathers information to point the gun at the most sensitive assets, and the Blue Team receives constant information on offensive activities.

This allows the Blue Team to test the effectiveness of security controls, use cases, or detection rules, and make adjustments on the fly, and then retest them in a sort of continuous testing, until the controls are proven effective throughout the threat’s Kill Chain.

Therefore, it is not the name that matters, but the attitude with which security and Red-Blue synergies are approached in an organization.

How is this implemented?

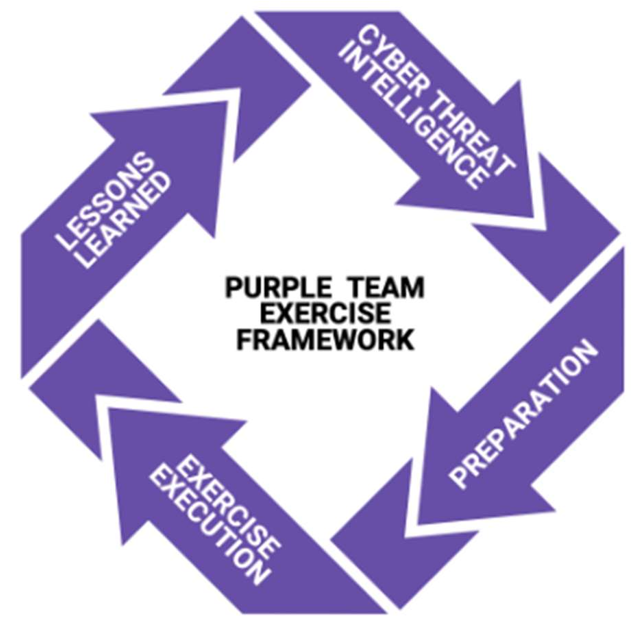

Before it was given a fancy name, many organizations were already applying this philosophy, but it has been in recent years that frameworks and standards have been developed to ease the burden of those organizations that are beginning to consider creating or modifying their security policy.

Depending on the maturity level of the organization, the Purple Team philosophy can take many forms, from sporadic exercises to a continuous audit program, fed back with new threat intelligence and lessons learned.

Methodology development

Once the basic concepts are clear, it is time to ground this methodology and put it into practice in defined and replicable steps.

One of the organizations with the most know-how in this area is Scythe, which has made available this document detailing the methodology they propose(Purple Team Exercise Framework), although it should be noted that it is closely linked to the entire MITRE doctrine and tools.

From here on, each of the steps that Scythe proposes will be presented, although today we will cover only the first one.

- Defining roles and responsibilities

- Threat Intelligence

- Preparation

- Execution

- Lessons learned

1. Definition of roles and responsibilities

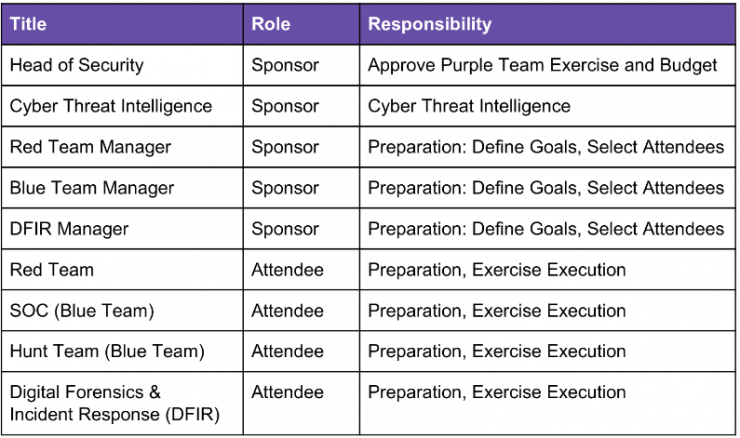

Sponsors

Before starting any of the actions defined here, it is essential to have the support of the managers of all the departments involved.

They should agree on the objectives, budget and scope of the exercise. Subsequently, the support of the operational managers should be sought, since their operations will probably be impacted by the dedication of analysts and operators to the exercise.

Therefore, they will be in charge of appointing the participating personnel and relieving them of other responsibilities.

Threat intelligence

A requirement for these exercises is the intervention of CTI, either in-house or outsourced, to provide actionable cyber intelligence in the early phases of the exercise.

The CTI team will be responsible for identifying adversaries with opportunity, intent and capability to attack the organization. It will also be responsible for obtaining details on the behavior, TTP or tools used by such adversaries.

CTI analysts can participate as bystanders during the execution of the exercise to obtain information about the organization (especially from the lessons learned phase), so as to better perform the task of identifying likely enemies for the organization afterwards.

Red Team

The competencies of the Red Team are very broad during the preparation and execution of the exercise.

The preparation is similar to that of a Red Team exercise. In this exercise, all the tools and procedures that will be used during the adversarial emulation must be configured and prepared. The use of automated tools such as CALDERA, Atomic Red Team or Infection Monkey is recommended.

Operational managers should appoint the participating personnel and ensure that they have the necessary availability.

SOC (Blue Team)

The SOC manager shall assist and appoint the participating personnel, ensuring that they have the necessary availability and eliminating other responsibilities, designating for this purpose other analysts to take the workload.

The participation of the SOC in the preparation of the exercise is minor, as most of their activities are carried out during the execution of the exercise. Organizations that do not have a SOC and have contracted the services of an MSSP must have the approval and participation of the MSSP.

DFIR (Blue Team)

Finally, DFIR specialists should also assist, although their involvement will be small in the preparation phase and much greater during the execution phase and especially at the end of each workflow iteration and evidence is gathered for a more successful next iteration.

The operational manager will be in charge of redistributing the workload to free up cases for the participants in the exercise, without affecting the rest of the cases.

Of course, the nature of each organization will determine how these roles and responsibilities are distributed, so that it is possible to combine more than one role in some person or persons and still maintain the independence of the coordinator of the Red/Blue team exercise.

With all responsibilities well defined, the next stop would be Cyber Threat Intelligence (an exciting topic), but we will leave that for a future article in this series.