Note 0: This series of articles is a description (hopefully entertaining) of the case study (fictional, beware) that Maite Moreno and myself presented at the c1b3rwall digital security and cyber-intelligence conference, organized by the Spanish National Police. If you want more information on CEO scams you can check the (in Spanish) slides of our talk,full of data as well as a real case that we researched.

Note 1: We emphasize that this case is fictitious. However, the techniques and procedures used are identical to those used by the attackers, with the difference that we offer evidence to study them in detail. Note that he investigation could have been done more efficiently, but we wanted to show some interesting elements and techniques to deep into Exchange, hence the steps taken.

Note 2: Before starting the case study… you can play it! We have set up an open-access forensic CTF you can use to practice your technical skills. Try it before reading these articles (recommended), or later to reinforce concepts. If you only want the raw evidence, you can get them here. You can also download the step-by-step guide with all the tools and evidence needed for each step of the articles, perfecto to continue with the slides.

Those of us who work in incident response and forensics would love want attackers to warn us before doing their wrongdoing. We want it together with the Lamborghini, the yacht and the unicorn with a rainbow in the background, but we get the same response in almost all cases: no f****** way.

“What a pain in the ass it is to have an incident at 14:55 on a Friday,” you would think. There are worse things: a call from your boss at 15h on a Saturday while you are taking a nap: “Grab your incident suitcase, ‘we’re going to party’».

The party consists of about 4 hours of travel from Madrid to Ponferrada, where the headquarters of the MINAF (Minerías Alcázar y Ferrán) is located. MINAF is a mining company that will not ring a bell, but which has a turnover of more than 40 million euros and operates in 12 countries.

The problem is quite simple: $100K have disappeared from their bank accounts. Obviously, they are slightly worried and want us to conduct an internal investigation before reporting it to the police. We talked to Abelardo Alcázar (CEO of MINAF) and Alfonso Ferrán (CFO of MINAF) and we managed to shape the following line of events:

- MINAF has spent months in negotiations with the government of Coltanistan (a former Soviet republic in the Middle East) to close a deal to exploit one of the world largest coltan mines.

- The negotiations were on track, and the CEO of MINAF traveled to Istanbul on June 7 to fine-tune the final details and sign the contract.

- Abelardo Alcazar lands at the Sabiha Gökçen International Airport at 13h., and arrives to the Ritz-Carlton hotel at 13:45h. At 14:30h, after a light snack, the final negotiations begin.

- At 18:00h, Alfonso Ferrán receives a series of emails from Abelardo Alcazar, urging him to make a set of international transfers worth $100K

- Around 18:30h Alfonso Ferrán makes the transfers.

- Around 20:30h Abelardo Alcazar finishes the negotiations with the Coltanistan government and sends an email to Alfonso Ferrán commenting that everything went as expected.

- Alfonso Ferrán responds by inquiring about the transfers, but Abelardo Alcázar assures that he did not receive that email (nor obviously demanded those transfers). He claims that around 20:45h on June 7, his phone started “doing strange things” and his access to the mail and contacts were deleted.

- Alfonso Ferrán tries to reach Abelardo Alcazar on Friday without any success. When he returns to Spain the next day around 14:00h, he manages to contact him and the fraudulent transfers are discovered.

- A security incident is declared at 14:30h. The CEO of MINAF contacts us and asks for our help.

The cybersecurity of MINAF is quite reasonable, considering that it is an SME of 100 employees with 2 computer scientists: all their computers have an antivirus and have the security updates up to date. Both mail and navigation logs are kept, and a cybersecurity awareness plan is being initiated for all employees. This is a much higher than average level that we are used to, in fact.

Although the case smells of a CEO scam, we don’t want to close ourselves off to any possibilities. It will not be the first time that some smart-ass tries to do a “the dog ate my homework” to the company, the insurance company or even the bosses/partners of the organization. It is our duty to act in a completely impartial way and gather all possible evidence to resolve the case as clearly as possible.

One of the good things about incidents is that everything you ask for (except the unicorn) is given to you almost immediately. In less than 5 minutes we are provided with the laptops of both the CEO and the CFO of MINAF, and a technician provides us with the local administrator account so that we can quickly launch both a RAM capture with winpmem and a data triage with CYLR.

Since we are dealing with a case in which email is critical, we boot the computers with a LiveUSB from DEFT Linux (a forensic-oriented Linux distribution), mount the laptop’s hard drive in read-only mode and get the Outlook folder of both computers, located at:

C:\Users\abelardo.alcazar\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Outlook\

The laptops remain in our custody in the event a forensic image is needed (right now, without knowing what has happened, it is better to put our efforts to obtain more information about the incident).

In this case we will go a little further in obtaining evidence from the mail. MINAF has its mail on an Exchange 2010 server on a VPS of a medium-sized ISP, that allows them administrator access without problems. Together with one of the MINAF IT staff, we connect using Remote Desktop and make an evaluation of the evidence we want to collect.

Initially we would like four types of evidence (if available). From highest to lowest level we can obtain:

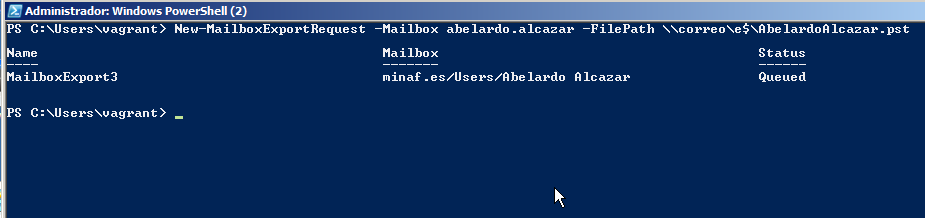

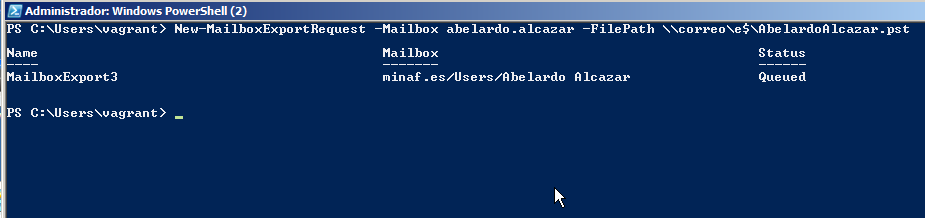

- Mailboxes: When we have an Exchange, it is usual for clients to have the mailbox synchronized against the server (that is the case in this incident). We can then get the mailbox directly from the Exchange with a bit of skill (and mostly, a little bit of Powershell):

- CAS Logs: Exchange has a frontend that manages all accesses to the server, which is called CAS (Client Access Server). In the CAS we have all the accesses, from the OWA to the Outlook clients (in addition to all the corporate mobile terminals). Luckily, the CAS actually has an IIS running underneath, so we will have all the logs in the folder: C:\inetpub\logs\LogFiles. The logs have a known text format, which will make it very easy to process them.

- MessageTracking Logs: MessageTracking is a high-level log that allows us to obtain the basic metadata of an email (origin, destination, date sent, subject, etc…), very useful to get a quick view of the emails. By default, the last 30 days are saved, but it never hurts to check the status on the server with a quick query:

- Indeed, they have the default value so we can operate and collect the last days of mail tracking with another Powershell query:

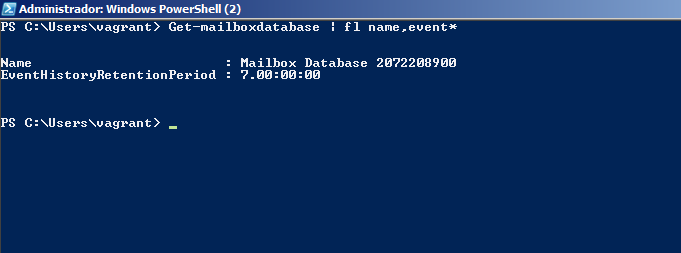

- EventHistoryDB Logs: The EventHistoryDB is the lowest level accessible Exchange log, and it obsessively stores a huge amount of data about the lifecycle of an email. Do you want to know when an email was received? What time it was opened? If it was deleted without having been read? EventHistoryDB answers all these questions and more. The downside is that by default it only saves 7 days of logs. We check that the default value is maintained:

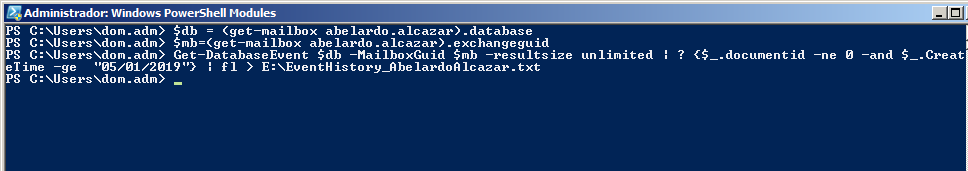

Default values again. In this case, the MINAF has been very quick to detect the problem and contact us, since only 24 hours have passed since the incident. We can retrieve this information with a couple of Powershell commands:

It’s almost 21:00h when we finish all the data acquisition. We leave a copy of all the evidence to MINAF (they will need it for the following police report) and, although Ponferrada is a nice city, we return to Madrid to start the forensic work on Sunday with a clear mind…

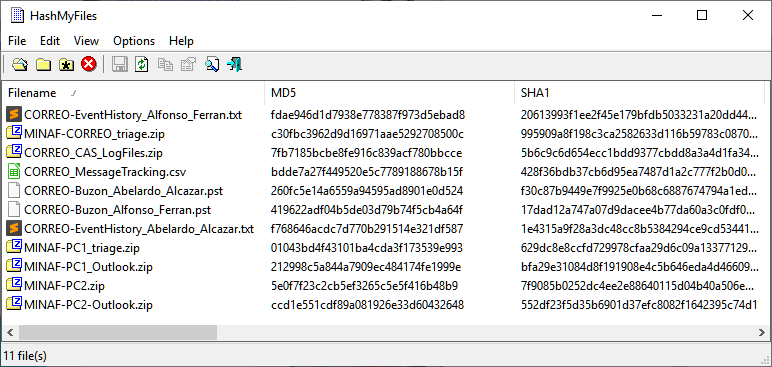

Indeed, on Sunday at 9h, with something more like a barrel than a cup of coffee, we begin the forensic analysis. The first thing is to verify that all the evidence is correct, so we calculate the hashes with HashMyFiles:

F***! The hash of the MINAF-PC1_Outlook.zip file (the mail of the CFO, Alfonso Ferrán) does not match the one collected in the evidence acquisition form. Since the USB has never left our hands it is impossible that it has been manipulated, but there may have been a problem with the USB that affected the file.

It is not a serious problem, because MINAF keeps the originals in its safe, but we won’t be able to access that evidence until Monday. We will need to be creative and see how we can overcome this lack of information in our research.

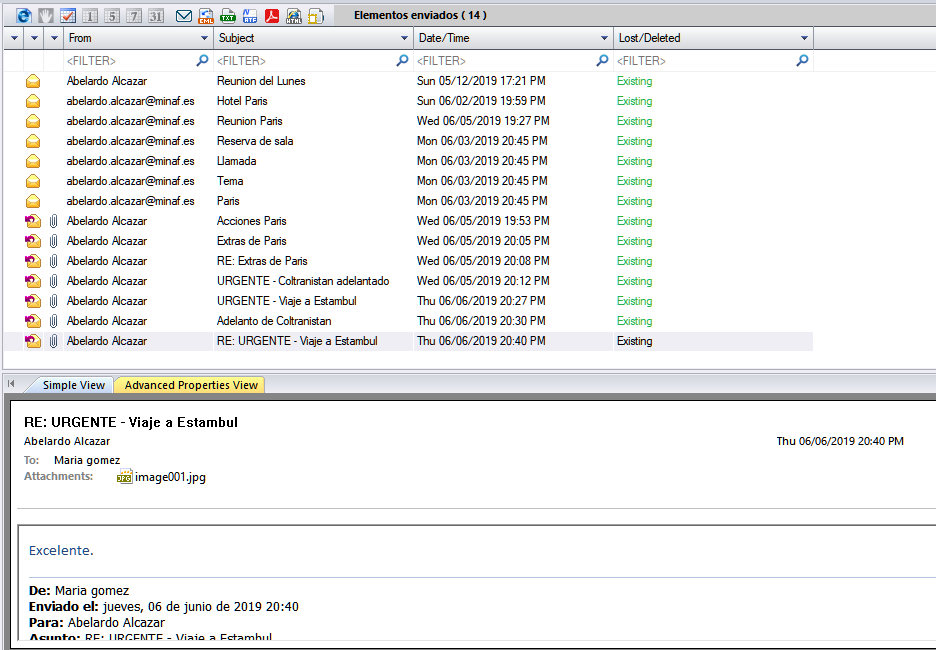

Let’s start with the email from the CEO, Abelardo Alcazar. Since we have his mailbox obtained from the computer (and since it is synchronized with the server, it should be the same everywhere), we open it with Kernel Outlook OST Viewer and check on it:

Mmm… no email from June 7 in the “Sent” folder. Nothing in the Outlook trash either. Let’s check what CFO Alfonso Ferrán’s email says:

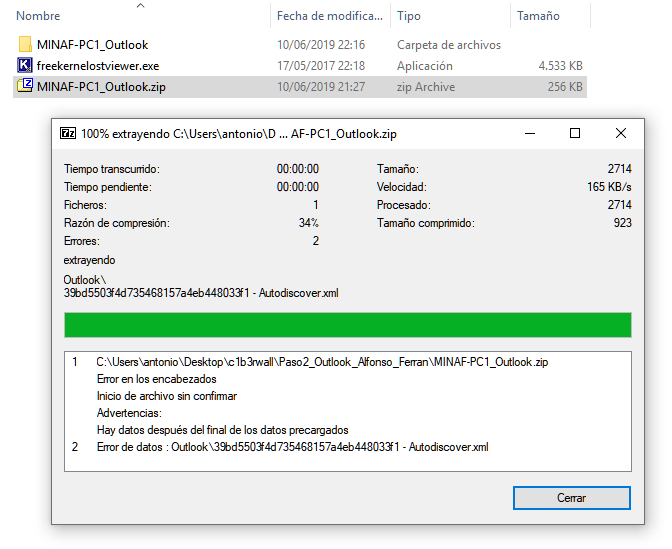

That’s why the hashes do not match: the file must have been copied wrong, or we have a failure in the USB, because the file is corrupt.

To advance in the analysis we will consult the MessageTracking logs, but that will be in the next post…