Editor’s Note: tomorrow morning our colleague Antonio Sanz is going to be giving a talk on the malware described in this post, and the handling of the incident associated with its detection at CCN-CERT‘s 8th STIC Conferences.

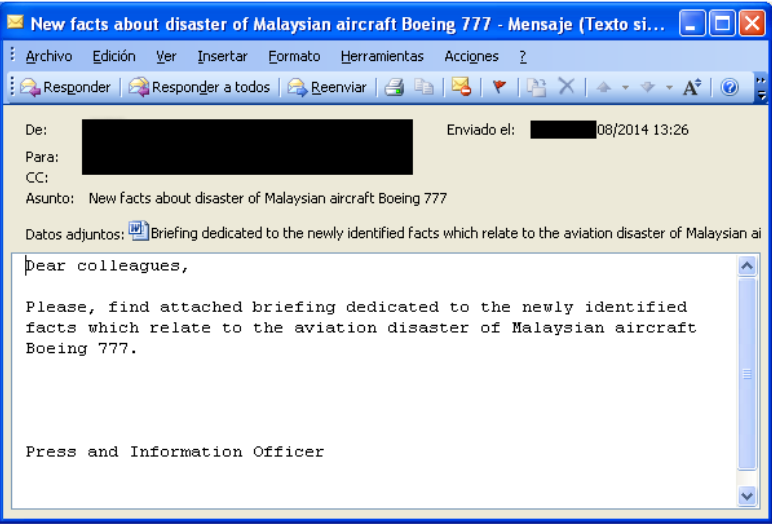

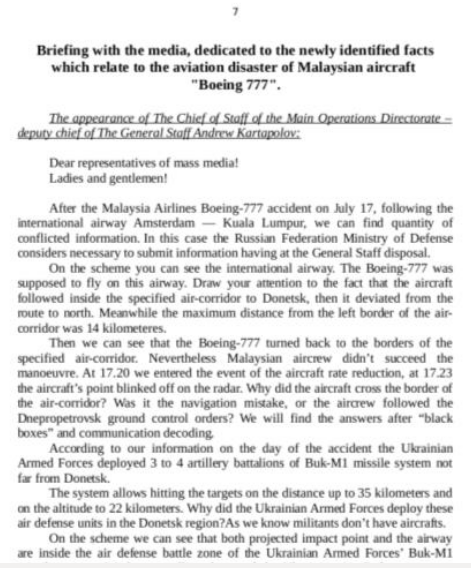

Last August, several possibly targeted employees of one of our customers (a strategic company) received a number of messages somewhat “suspicious” that concerned the then relatively recent crash of the Malaysia Airlines plane.

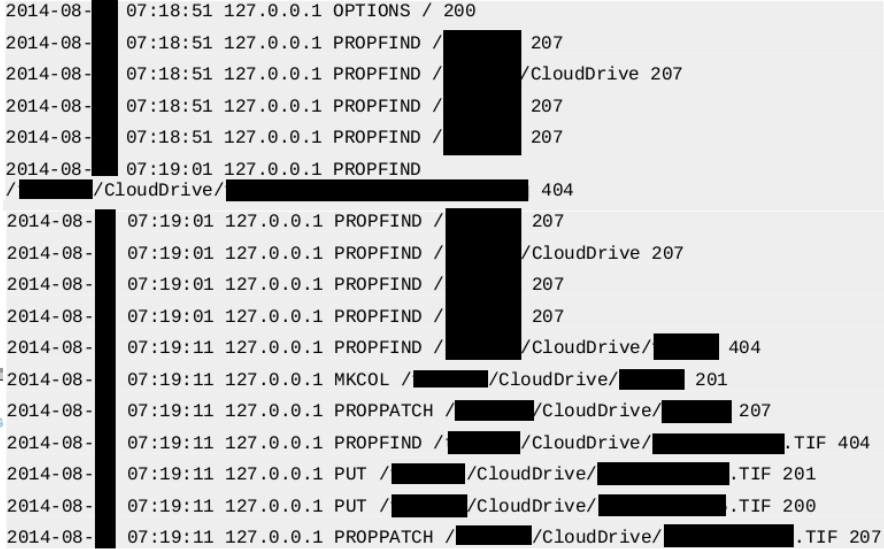

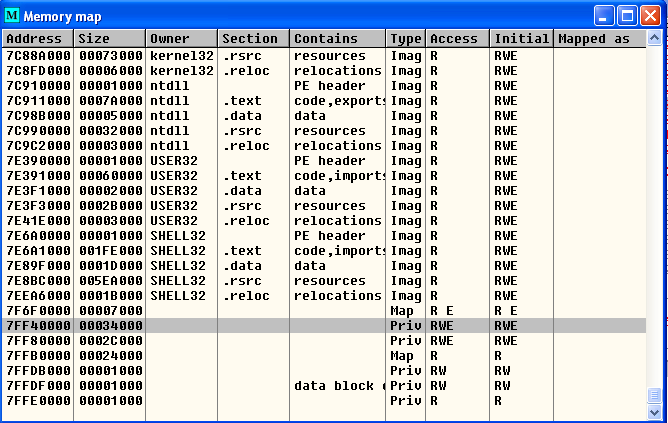

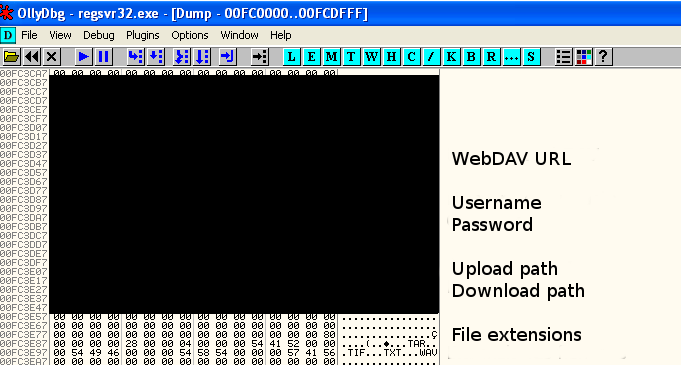

After about 12 minutes (!) waiting, the sample finally tried to contact something, and, to our surprise, that something was a public WebDAV provider service. So the malware used that protocol over HTTP (and not over HTTPS, according to the results of our latest tests), for anything it was trying to receive, or to transmit…

Indeed, simulating the WebDAV server to which it was trying to connect in our lab, the sample was trying first to download information from a particular path inside the WebDAV, and then it uploaded into another path some pseudorandom named files (but with known file extensions).

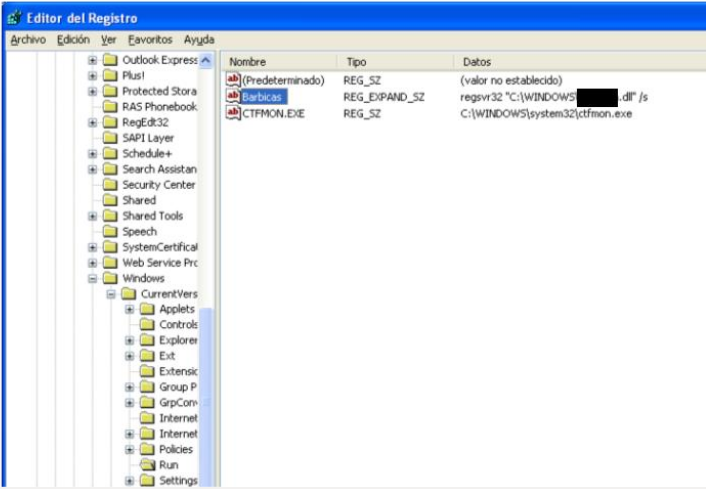

This DLL (dropped directly into %SystemRoot% if the user had the necessary privileges, or into the user’s profile otherwise) was loaded using the Windows command regsvr32, persisting through an invocation of that command on the usual HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run registry branch. For this attachment, the key was written with the name Barbicas (a word resembling “small beard” in spanish).

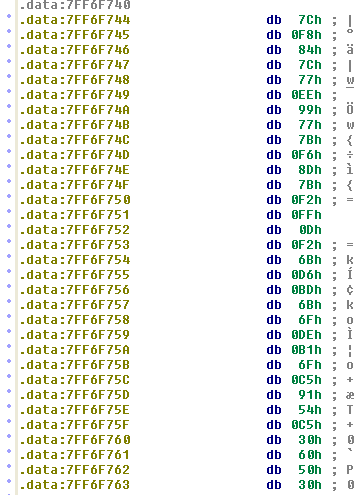

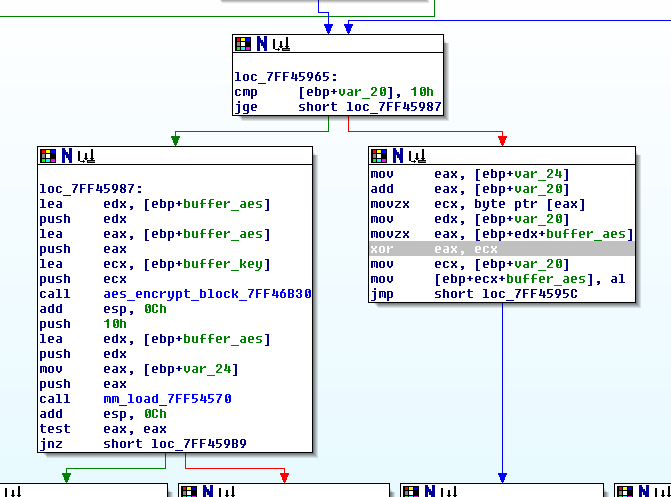

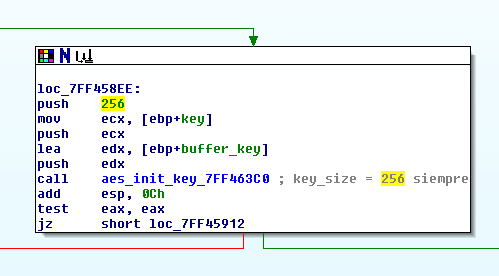

So far, we had an unknown malware, capable of connecting to an Internet WebDAV server (an original protocol, in comparison to other documented campaigns), and capable of both downloading (command and control channel) and uploading (exfiltration channel) AES-encrypted information (with a 256 bits key length) from/to different paths of the WebDAV.

But the surprises were not over yet; after analyzing the remaining attachments (remember that several users of the organization received malicious messages), we saw that each one was different from the others:

- The dropped statement about the plane crash (the “clean” document) turned out to be the same for all attachments

- Both the dropped .vbs and DLL were distinct for each message (both the DLL name, always trying to imitate some legitimate Windows DLL, and the DLL file contents)

- The registry key used (Barbicas for the first sample analyzed) was distinct for each dropper

- Unpacking time was also distinct for each attachment, varying from 8 minutes to more than 15 minutes (in any case, the process was keeping one of the CPUs at 100% usage)

- The WebDAV server was the same for all samples, as well as the username and password used to log into it (which it does not mean that, for other possible victim organizations or campaigns, were not generating artifacts that used another credentials)

- However, both the AES 256 bits key and the upload (exfiltration) and download (command and control) paths were different for each analyzed sample (in all cases, all that information was present in the memory of the unpacked DLL)

- The extensions used in the uploaded files (.TAR, .TIF, .TXT, etc. for the first attachment analyzed) were distinct for each sample

Therefore, it’s clear that what we saw was probably a possible campaign using (so far) unknown malware, and selecting the victims in a highly targeted way. The attackers used some kind of artifact generator; once a copy is generated, it uniquely identifies the victim as well as the exfiltrated information, by its use of distinct accounts, directories, file extensions and AES keys for each mutation. Furthermore, it is clear that this was almost certainly the first phase in what could have been a longer persistence in the victim organization.

We don’t know what it would have been possible to find after a few weeks, or months, of effective compromise.

Update: on December 8, 2014, Symantec (re)codenames the malware (or at least one of its mutations) as Infostealer.Rodagose (Number of infections: 0 – 49, Number of Sites: 0 – 2). We still prefer Barbicas :-)

It’s been over 4 months since we saw the malware for the first time and an AV vendor has begun to to detect it (and so far, we are not aware of more public presence), reporting “few” infected sites (therefore, is it a campaign that has affected several organizations?); the above, and the character of the highly targeted victims we saw in the case of our customer, maintains the “enigma” for the moment. We will try to keep you informed as more information emerges.

Update 2: on December 9, 2014, Blue Coat publishes a report, (re-re)codenaming the malware as Inception. All information in the report is consistent with what our team observed in August 2014. It seems clear that it’s an APT campaign.

Update 3: on December 10, 2014, Kaspersky codenames it Cloud Atlas.